April 1975, Phnom Penh - Saigon

This exhibition examines fragments of the lives and work of the journalists who covered the final few days of the wars in Cambodia and Vietnam in April 1975.

The wars in Indochina were not only defining moments in history, but they also produced journalism that, for many, became the mythic benchmark against which all that followed was judged.

These conflicts were the first fought under the ever-present glare of the press. Magazines and newspapers have never had more influence than they did in the 1960s and 1970s. Radio brought the war to our commute to work and into the kitchen while we were preparing meals for our families. For the first time, war could be broadcast in full color into our living rooms, so we could watch the horror from the comfort of our own sofas.

In Vietnam, the news was reported by journalists accredited to the military who could fly on helicopters to the frontline and return to their hotel for drinks at night. They wrote with pencils in notebooks, typed up their stories in the afternoon and then telexed them to newsrooms in Paris, New York, London and Tokyo to meet deadlines. Photographers went to battle with pockets stuffed with film cartridges; these were shipped in envelopes with handwritten captions to clients overseas, or processed locally — sometimes in hotel bathrooms — and then transmitted down phone lines from the post office or Radio Saigon. TV camera crews shot film and shipped their reels to Hong Kong or Tokyo to be processed and edited; they would then either be transmitted by satellite or shipped again to Europe or the USA for broadcast days later. It feels slow now, but it was electrifyingly fast at the time.

Neighboring Cambodia was the most dangerous place on earth for journalists in 1970. Because helicopters, the workhorses of the U.S. war in Vietnam, were not available, reporters and photographers traveled unescorted to and from the fighting down eerily empty roads in private cars. Many fell victim to ambushes by communist forces. In an eight-week period in April and May 1970, out of a press corps of about 60, some 25 journalists disappeared or were killed.

Despite all the risks, Vietnam and Cambodia attracted journalists like few other wars have since, and for many, it was the defining experience of their lives. As the great Neil Davis said, “I formed the strongest personal relationships of my life in Indo-China and unfortunately I lost many of those friends killed in Cambodia and Vietnam. It’s very difficult to recapture that feeling of comradeship I had with so many people there. In a sense, when I had to leave Indo-China, a good part of me died.”

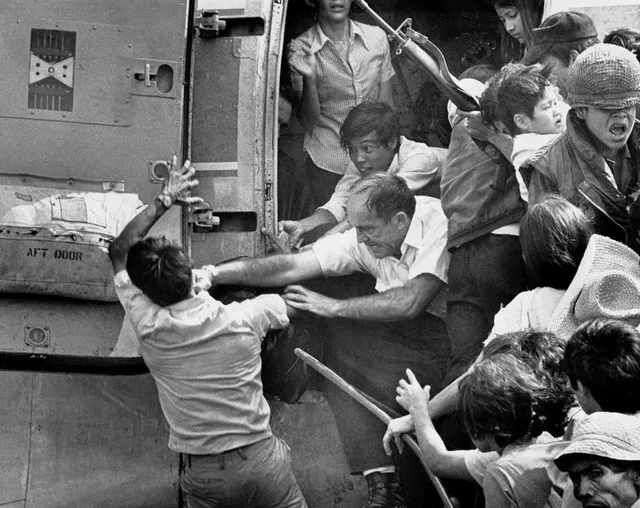

Few could divine the undercurrents of war better than the journalists who had been reporting from the frontlines for years. Yet, when the decades-long war came to an end, it came so fast that life-changing decisions about whether to stay to the end or evacuate had to be made in a matter of hours. Some raced for the last helicopter out, and some raced for the last plane in. Some were able to rescue loved ones as they fled; some had to leave everything and everyone behind.

Those who stayed bore witness to the greatest story of their lives, many of them making reputations that endure until now. This exhibition is dedicated to those who died trying, including 31 Cambodian journalists killed by the Khmer Rouge when the war was over.

Jon Swain and Gary Knight

Bayeux. September 2024.